My dear friend Maureen was on the Continent this winter, and, as I usually do when an American friend crosses the Atlantic, I chose to meet up, this time, in Andalucía. I understand that visiting this part of Spain in warmer months is out of the question with climate change — even here in Provence the heat is intolerable. So, a January holiday turned out to be a good idea. The bonus was the paucity of tourists (there were still quite a few in the popular spots, like the Alhambra).

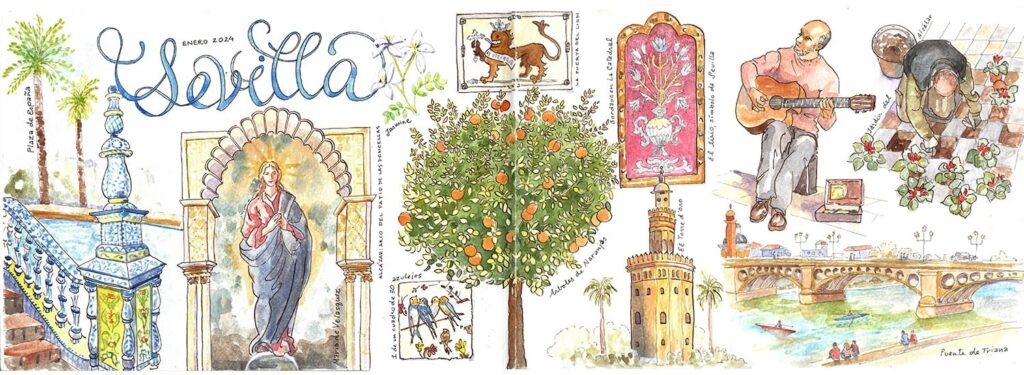

Our first stay was in Seville, where we had a luxurious apartment in the Arenal district, near the subsidiary arm of the Rio Guadalquivir, the Torre d’Oro, and the bull-fighting ring (though that would be the last place I’d visit). We were very close to the Real Alcázar—meaning royal castle (spanish + arabic) — which was the site of our first tour.

Sevilla is a glorious city. I loved the feel of it—expansive, riparian, and very clean! I got a crook in my neck from looking up. Lavish architectural details: turrets, colorful ceramic details, and almost the only rubbish I saw littering the streets were dead oranges that had fallen from the ubiquitous orange trees. Maybe because it was so off-season, our encounters with the inhabitants were pleasant and polite. The weather was cold in the early mornings (and, because we were so far west in the mid-european time zone—UTC+1, the sun didn’t rise ’till 8:45!, so dark, too) but warmed up as the day progressed, especially on the sunny days. Only a very few sprinkles.

We went everywhere by foot. My favorite walk was that which we took to the Parque Maria Luisa. I believe the street we walked along is the Avenida Menendez y Pelayo, which was lined with a generous pedestrian way. All along this are trees, tiled benches, and a wide, hard, sandy path for the walkers. At the end of this street is a marine monument to Christopher Columbus and the glory days of Seville, before the river silted up, when the city was the center of colonial trade.

At the Museo Hospital de los Venerables, founded in the 17th century as a home for old priests, there is a tiny “Centro Velasquez”. Only three paintings are by the artist, one an unusually mystical Virgin Mary, and a second which shows a view of Sevilla from the other side of the river. You can see the golden Torre del Oro, the cathedral, and the floating bridge (built by the Moors), which was replaced by the pretty Triana Bridge, beside which we enjoyed the setting sun, along with post-work Sevillians, and other tourists. Because the painting is so terrific have included an image I swiped from the excellent educational website, Khan Academy.

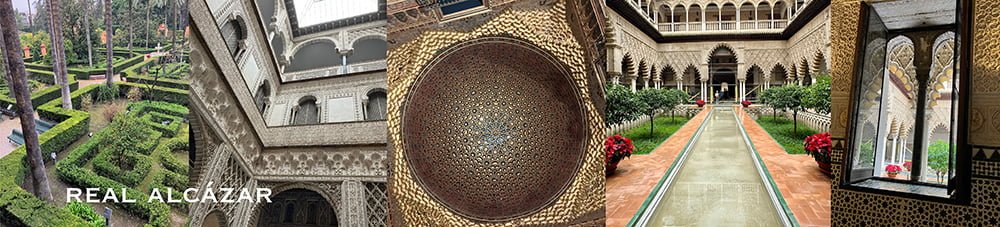

We took an extended personal tour of the Alcázar and the Cathedral (the two are joined at the hip, The Giralda bell tower was originally the mosque’s minaret) on our first day. This turned out to be a good way to introduce us to the importance of the Islamic period in Spanish history, and the melding of the muslim and christian cultures. By the 10th century the entire Iberian peninsula had been conquered by Arabs and Berbers, Yemenites and Syrians. It was called Al-Andalus, and the new Caliphate was Córdoba. The following few centuries brought many conflicts between the existing population and the Muslims, and by the mid-13th century, only the Emirate of Granada remained as Muslim-held. The Alcázar palace was started in the 10th century but was elaborated by Seville’s Almohad rulers in the 12th century. So beautiful and lavish it was that, when the city was conquered by Castilians in the 13th century, their rulers made it the royal residence. Pedro I was the king most associated with the palace. For Pedro, adopting Moorish ways, with Arab sayings engraved all over the walls seemed the best way to appear a powerful king (like his pal Mohamed V of Granada). He used “mudéjar” arab craftsmen (meaning “tamed” arabs) to expand the palace.

Over the period of the Alcázar’s construction, Andalucía was the home of three religions—Jewish, Muslim and Christian. In some of the tile work, we can see the symbols of these 3 co-existing harmoniously: the 6-pointed Star of David, the 8-pointed Muslim star, and the Christian cross. Those harmonious times didn’t last long: in the 12th century, a fundamentalist Islamic regime offered the choice between death, conversion or expulsion. Later, when King Ferdinand II & Queen Isabella (of Christopher Columbus fame) conquered the last Islamic strongholds, they offered the same choice to Muslims and Jews. As the Real Alcázar continued to house Spanish kings for 7 centuries, the symbols of Ferdinand (“Tatamota“—meaning “the end justifies the means”), Isabella (arrows), and the double-headed eagle of Charles V & the Hapsburg empire adorn various walls. The Puerta del Leon announces the king is “ready for everything”.

Something that struck me again and again in this part of Spain, was the love of repetitive pattern. We saw it in the complex arabic plasterwork, the orderly gardens (where even the cyclamens are planted on a grid cut out of ground cover fabric) and in the ubiquitous ceramics. At the Alcázar, we were introduced to the complex tile work we saw throughout our visit to Andalucía. The earliest patterns were made using a mosaic technique where each tile is a different color and/or shape. For azulejos the colors are separated either physically, using a cloisonné technique (called cuenca — bowl, basin), or chemically, using a strip of manganese carbonate & grease (called cuerda seca — dry rope). This way colors can appear on the same tile. In the Muslim religion it is forbidden to represent people or animals, so geometric patterns are the go-to decoration. In addition, the color palette is to be limited to gold (or ochre), representing the sun, green for vegetation, blue for the sky and water, and black for earth. I found an interesting post about these tiles, if you are interested, here.

I particularly enjoyed the gardens, carefully laid out with rows of palm trees and topiaries. We were told that in an arabic garden one needs to have a water element, a visual element, a taste element (oranges or pomegranates) and a fragrant element. Within the entrance to the Alcázar are sunken gardens—the better to have the blooming orange blossoms level with your nose. Our guide explained that arabic fountains are quiet, just tranquilly leaking water to their basins, whereas fountains of the Christian heritage make splashy noise. Hmm…

Across the river, in the Triana district, was home base for the ceramic factories back in the day. All but one moved out of the city (probably for health reasons: all those heated glazes…). There is a museum dedicated to the tile industry, the Centro Ceramica Triana in an old ceramics factory. There, we were able to see historic 2-storey kilns (fire downstairs, heating shelves of ceramic ware above), and lots of antique tile advertisements and artistic pieces.

The most impressive display of tiles is at the Plaza de España, a magnificent world’s-fair-style park built for a 1929 Ibero-American Exposition. A half ring of water curves around a series of alcoves, each representing, in elaborate ceramic, one of Spain’s provinces. 4 beautiful (with ceramic balustrades) bridges arch above the waterway, over which holiday makers can row.

Andalucía is home to flamenco, and Sevilla has a museum dedicated to the dance. When we visited, we could see a sweatpant-attired dancer practicing her breathtaking footwork. There was artwork inspired by flamenco, and even a couple of floorboards displaying the wear and tear of stomping feet. Like tango in Argentina, flamenco is taken very seriously in this part of Spain, and there are different styles, schools of dance and influences. And lots of shops that cater to the dancers, with flouncy, polka-dotted dresses, silky shawls and colorful fans.

Food. As a vegetarian (and occasional pescatarian), I was challenged. Like the Argentinians, these people like their meat. As it wasn’t summer, salads were rare, and cooked vegetables rarer. I love fried food, so some of the non-meat tapas (they were very good at Casa Morales) were lovely to begin with, but after a couple of days of fried potatoes, I craved something green. I made do with an artichoke here and there, and brought avocados back to our apartment to have there. However, if you spend some money, you can get a fine meal. We had a delicious lunch (custom of the country is lunch at around 14:30) at La Casa de Maria on the day we walked across the Triana Bridge. We also enjoyed some cake and coffee outside Cafe Cappucino Grand Cafe. One day, having eaten an unsatisfactory lunch at a restaurant decorated with the heads of bulls along the walls, we, along with all the rest of the tourists, had churros and chocolate at the Cafe Bar El Comercio.

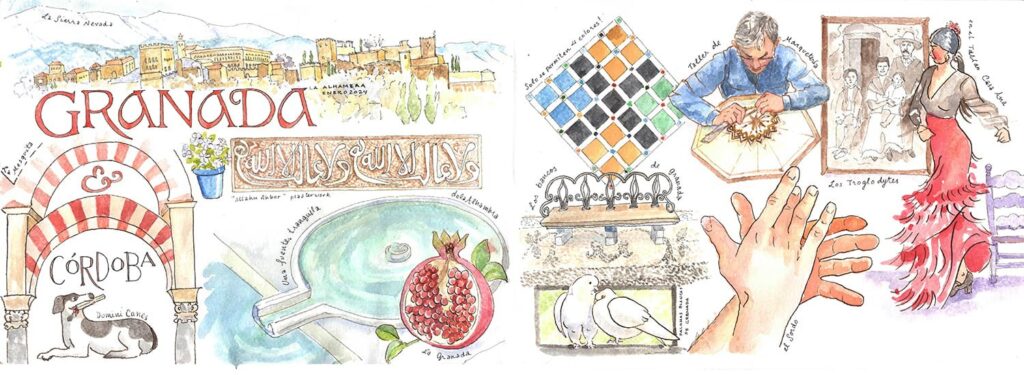

Originally we planned to visit only Sevilla and Granada, but a couple of friends convinced me that it would be a shame not to make a quick visit to Córdoba, conveniently about halfway between, to see the magnificent Mezquita. Renfe is the Spanish train system, and it is pretty darn great. From their app we bought our tickets to Córdoba.

The town is situated upstream on same Guadalquivir river that runs through Sevilla. While waiting for our assigned time at the Mosque, we walked across the Roman bridge to enjoy the view.

The enormous Córdoba Mezquita-Catedral (mosque with a cathedral plunked in the middle) is impressive. You enter a forest-like space of double arches, receding back into the shadows. It was built for Abd al Rahman I, founder of the Islamic Emirate. When Christian forces captured Córdoba in the 13th century it was converted to a cathedral, and in the 16th century a grandiose nave and transept were inserted into the complex. Architecturally, this was an unfortunate addition. Ok for the chapels that line the old mosque, with a cross here and there, but that imposing confection in the middle really dampens to spiritual atmosphere of the ensemble. I did like the statue of St Dominic, who had had a vision of a dog bearing a torch. The latin, “Domini canes” is the Dominican order’s play on their name meaning “dogs of god”.

We carried on to Granada that evening, where we had rented an apartment in the center of town, near the cathedral.

Granada is hilly, and the snowy Sierra Nevada mountains stand picturesquely behind the dominating Alhambra. A dribbly stream, the Darro, runs through town. The citadel is situated on a tall promontory above the narrow streets of town. The site was obviously chosen for its strategic advantage, but also for all the streams, coming from the Sierra Nevada behind, that make the land habitable. The fountains of the Alhambra and its Generalife Gardens are justifiably famous.

Al-qal’a al-hamra means red fort, and was originally built in the 8th century, before the Nasrid dynasty, for which it was expanded. Naturally, the first section to be built was the Alcazaba, the fortress part. The 13th century turned the fortress into a royal residence for Mohammed ben Al-Hamar (Mohammed I, friend of Pedro, of Alcázar fame). His descendants built up all the beautiful bits. Later, with the demise of the Islamic kingdom of Granada in 1492, the Alhambra was adjusted for the Christian kings, notably good old Emperor Charles V, also having altered the Alcázar, who built (still not completed) the massive Renaissance Palace in the middle of the complex.

Across from the Alhambra is the Albaiacín barrio, the moorish, medieval section of town which weaves its way up and around the hill. The Mirador de San Nicolás esplanade gives the best views of the Alhambra, and there were plenty of tourists and their accompanying street artists on the plaza. The tangle of narrow alleyways and stairs are picturesque and open up, on occasion, to pretty, stone-cobbled plazas.

Even further up the hill are the famous cuevas del Sacromonte, where Muslims, Jews, Moriscos (converted Moors), African slaves and Roma people made a community away from persecution, fitting out the natural caves into habitable dwellings starting in the 16th century, a particularly inhospitable period. The museum complex has preserved some of the homes, furnishing them with period furniture and accoutrements. Some people continue to live, troglodyte-style, in homes of varying degrees of cave-ness, some quite well appointed.

I regret not having gone to one of the tourist flamenco shows given in the caves. The Roma (gypsies) developed a unique style of dance called zambra, and their songs are full of the angst of persecution and poverty. I wasn’t feeling 100%, so during this trip I didn’t have the energy to take advantage of nightlife. In Granada we did manage an show at close-by flamenco center. The dance is intense and not particularly graceful. I loved the effects of the palmas (clapping of the hands— fuertes: flat for a sharp sound, or sordas: cupped for a muffled sound). When we were at the Sacramonte museum, a few old (from the ’40s, ’50s and 60s) movies ran on a loop. Seeing tiny children executing the complex dance moves made a big impression on me. We also saw films of some of gypsy flamenco’s historic greats. And they were. There is nothing like the expression of passion flamenco achieves. But I wasn’t in love with the singing, I regret to admit. Hearing those raspy voices gave me a sympathetic sore throat.

The trip was wonderful. I fell in love with Sevilla (I love rivers), and only wish the folks of Andalucía hadn’t so quickly switched to English when they heard me asking something in my abominable accent!

Wonderful!

Diana I felt almost immersed into your holiday as I recalled scenes and experiences from my own memory of visiting Seville and Granada (sadly not Cordoba) far too many years ago – love all the detail – even the clapping of the dancers hands … beautiful!

The accompaniment of your beautiful illustrations make your recollections a joy to behold – as always. Thank you for sharing.

Thank you Fiona, your comments are so encouraging—especially coming from you, whose taste I so admire!