I, along with my nephew’s wife Ellen (with whom I met up whilst on Skye), had been intrigued by the depictions of the Hebrides in the Peter May detective trilogy. Since I also have always longed to see the stark landscapes of Northwest Scotland, these were enough incentives for me to take the complicated trip up there.

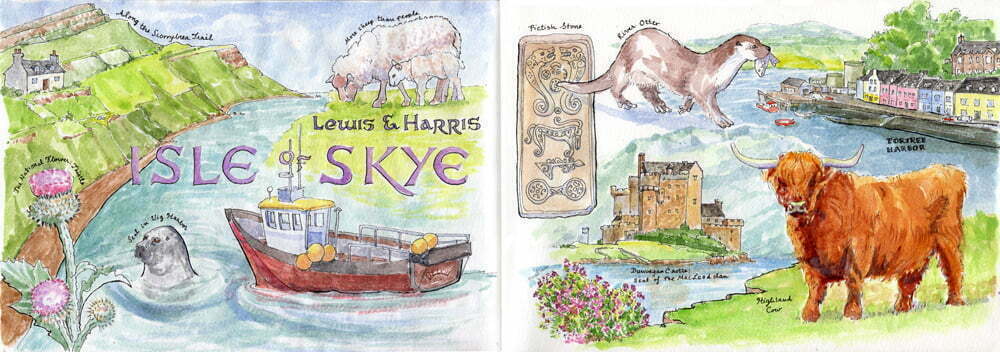

Skye is a large irregularly shaped island to the northwest. The name comes from Norse, meaning island of clouds. To the west are the outer Hebrides islands. In 1995 a bridge enabled easier access to beautiful Skye; the Hebrides are too far for a bridge, and you need to get there by ferry.

Flying into Edinburgh, I was able to situate the town in the crux of the Firth of Forth coming off the North Sea. This was my first encounter with the dominance of the water element here. There are Firths (narrow inlet or bay), Sounds, Lochs (inlets of the sea as well as fresh water lakes), Kyles (straits), Burns (stream), Invers (rivers), ponds, waterfalls, rain and mist. (I wasn’t there for the snow.)

The landscape is riddled with waterways thanks to the receding glaciers of the last ice age.

Willie, our well-versed and charming Scottish tour guide, drove about 12 of us tourists through the Island, showing us the best spots and giving us historical background in between stops. He also pointed out famous location spots for movies like “Skyfall” and “Outlander”, and gave us the mostly true history behind “Braveheart”.

We visited the remains of an ancient Broch, a defensive tower where a community of Picts could shelter 2,000 years ago (See Scotland I). One can still see the pre-clearance strips of communal land cultivation (Run rig). Also still visible are the ravaged stone foundations which gained meaning when Willie explained about the terrible clearances, when 18th and 19th century landlords, on whose lands the old Scottish clansmen farmed and lived destroyed the homes of the highlanders, calculating that populating the fields with sheep was more profitable.

The stark landscape of the Highlands, Skye and Hebrides is mostly due to the lack of trees, which were all harvested long ago and never came back, except for the farmed trees that one can see stripped away at maturity.

The Highland Mountains are not that high (the tallest, Ben Nevin, is only 1,345 meters) as they have been eroded from their former, volcanic and spiky glory, like their cousins in Appalachia. What is now Scotland started off down at the South Pole, which was verdant and tropical at the time (that’s where the petrol and coal comes from). And apparently the country is still migrating north.

The father of modern geology was a Scot: he proved that, contrary to religious beliefs, the earth was a helluva lot older than what the Bible claimed. Scotland is a puzzle of multiple rock formations and many forces working them. The sandstone of which Edinburgh is constructed was laid down on the shallow seas that covered the land. Tortuous volcanic activity kneaded granite into the oldest rocks of Scotland: James Huttonthe 3 billion year old Lewisian gneisses, a small souvenir of which I’ve brought back to France. Basalt towers formed the dramatic Kilt rocks on the east coast of Skye. All the different formations suffered the sculpting of glaciers. The Red Cullin (from Gaelic for mountain range)are made of granite, which is softer that the igneus gabbro of the pointier Black Cullins (including the Old Man of Storr), and present a softer silhouette.

I love the color palette of Skye and Lewis: Heather, thistle and foxgloves matched in purple/magenta, the bright green grass and ferns covered almost-black peat, and the skies were always dramatic, with spots of blue brightness pushing through ragged grey clouds.

Between staying in Edinburgh and the isle of Lewis I lodged in the charming town of Portree, the biggest on Skye. My hotel was minutes away from a delightful hike along the coast, the Scorrybreac trail. Walking this trail alone was a great antidote to the peak-season mob scene in Edinburgh. Crossing a little stream at the beginning of the trail, a river otter surprised me, running across my path.

My nephew and his family picked me up in Portree for us to take the ferry over to Lewis together. The landscape and weather got harsher, which made a dramatic background to visit the mysterious Standing Stones formed with pillars of Lewis gneiss, which like Stonehenge are still not understood.

I returned to Edinburgh by bus and train via Inverness, which I have to say is not worth the visit.

I would like to return to this part of the world in the less-busy autumn, perhaps to stay put in one location, to paint.

Seems like a wonderful exploration of the islands Diana. Beautiful illustrations and photos as well as history and descriptions – all with more of those incredibly poetic names (I was compelled to look up ‘Firth of Forth’). It’s oh so incredibly green and wet up there, which is no surprise! Very enjoyable read. FD

Thank you Fiona for visiting my site. I mostly use it just to download after having experienced a new culture, and just to keep track of my paintings, so it is super nice to actually have someone whose opinion I value come and look. Thank you for your nice commentary!